L'Atlas historique du Québec

Travaux menés par une équipe franco-canadienne animée par Gérard Fabre, chercheur du Centre national de la recherche scientifique (CNRS) à l’Institut Marcel Mauss, École des hautes études en sciences sociales, à Paris, Yves Frenette, titulaire de la chaire de recherche du Canada de niveau 1 sur les migrations, les transferts et les communautés francophones, Université de Saint-Boniface, au Manitoba, et Mélanie Lanouette, coordonnatrice du Centre interuniversitaire d’études québécoises.

Les récits de voyage et de migration que nous sélectionnerons seront publiés au fur et à mesure de leur intégration au chantier La francophonie nord-américaine. Les premiers textes ont été intégrés progressivement à partir de 2018. D’autres, en préparation, suivront et élargiront le champ initial à d’autres périodes, milieux et types de scripteurs. Nous tenons à remercier le CIEQ pour son soutien irremplaçable et pour les compléments iconographiques et cartographiques des récits présentés.

- SOMMAIRE

- Fabre, Gérard, avec la collaboration d’Yves Frenette, Récits de voyage et de migration: une nouvelle anthologie

- Fabre, Gérard, Thérèse Bentzon, une féministe française catholique en Amérique du Nord, 1897

- Gallichan, Gilles, Olivier Robitaille aux États-Unis (Nouvelle-Angleterre), 1837-1838

- Frenette, Yves, Lorenzo Létourneau, un Canadien français au Klondike, 1898-1902

- Parent, Frédéric, Journal de voyage de Léon Gérin à Chicago et dans l’Ouest canadien en 1893

- Fabre, Gérard, Édouard Montpetit en Californie, 1918

- Fabre, Gérard, Le juge Pouliot en Europe, 1894

- Balloud, Simon, Augustin Leroy, un religieux français en exil en Amérique du Nord (1903-1918)

- JAUMAIN, Serge, André Castelein de la Lande: un Belge dans le Grand Nord Canadien au tournant des XIXe et XXe siècles

- LAPORTE, Dominique, Les voyages de la Liaison française au Canada (1924, 1925, 1927): anthologie d’écrits journalistiques

- HALLION, Sandrine, D’un village de Savoie à Haywood au Manitoba: le récit de migration de Jean-Louis Picton (1904-1913)

- Angers, Stéphanie, et Yves Frenette, Du Saguenay au Vermont, le récit d’émigration de Jean Angers, 1916-1920

Based on the work of an international team of scholars led by Gérard Fabre (CNRS researcher at the Institut Marcel Mauss, École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales, Paris), Yves Frenette (Level 1 Canada Research Chair on Migrations, Transfers and Francophone Communities, Université de Saint-Boniface, Manitoba) and Mélanie Lanouette (Coordinator, Centre interuniversitaire d’études québécoises, Quebec City)

We will periodically publish selected travel and migration narratives on then Atlas historique du Québec(CIEQ) website, in La francophonie nord-américaine. The first texts were posted in 2018. Other content,currently being prepared, will follow. It will expand the scope of the collection to cover new periods, contexts and types of authors. We wish to thank the CIEQ for its invaluable support and for providing iconographic and cartographic elements to accompany the published narratives.

- Summary

- Fabre, Gérard, in collaboration with Yves Frenette, Travel and Migration Narratives: A New Anthology

- Fabre, Gérard, Thérèse Bentzon, une féministe française catholique en Amérique du Nord, 1897

- Gallichan, Gilles, Olivier Robitaille aux États-Unis (Nouvelle-Angleterre), 1837-1838

- Frenette, Yves, Lorenzo Létourneau, un Canadien français au Klondike, 1898-1902

- Parent, Frédéric, Journal de voyage de Léon Gérin à Chicago et dans l’Ouest canadien en 1893

- Fabre, Gérard, Édouard Montpetit en Californie, 1918

- Fabre, Gérard, Le juge Pouliot en Europe, 1894

- Balloud, Simon, Augustin Leroy, un religieux français en exil en Amérique du Nord (1903-1918)

- JAUMAIN, Serge, André Castelein de la Lande: un Belge dans le Grand Nord Canadien au tournant des XIXe et XXe siècles

- LAPORTE, Dominique, Les voyages de la Liaison française au Canada (1924, 1925, 1927): anthologie d’écrits journalistiques

- HALLION, Sandrine, D’un village de Savoie à Haywood au Manitoba: le récit de migration de Jean-Louis Picton (1904-1913)

- Angers, Stéphanie, et Yves Frenette, Du Saguenay au Vermont, le récit d’émigration de Jean Angers, 1916-1920

Travel and Migration Narratives: A New Anthology

This anthology primarily aims to showcase unpublished or rarely circulated narratives. We will reproduce the most significant excerpts from each text, preceded by a short biography of the author. Our project therefore differs from classic anthologies insofar as it takes a broader approach to cultural otherness and its representations. Embracing a diverse range of social contexts beyond the world of professional writers, we use the term “narrative” to refer to a form of ethnographic objectification at the heart of discursive activity, one that narrates the twists and turns of a particular voyage by naming and describing the places and people encountered. This ethnographic dimension is key to our understanding of narratives. We refrain from defining the genre from a purely structural perspective, as is often the case in literary studies (Genette 1972; 1980)1In establishing his three categories, Genette duly recognizes the polysemy of the term “narrative”. Thus, he proposes distinguishing between the narrative as utterance (or narrative text), the narrative as story (or diegesis) and the narrative as communication (“the productive narrative act”, which includes the real or fictional circumstances in which the discourse is produced). Narratology studies the relationship between these three elements, an exercise that does not fit within the historiographic perspective of our anthology..

And yet, literary scholars do not have a monopoly on classifying texts and separating the wheat from the chaff: for a long time, historical scholars limited themselves to producing biographies of prominent figures who had left behind a record of their movements—most often in the form of documents written by these figures themselves, their companions or other correspondents with knowledge of their travels.

Meanwhile, anthologists were expected to focus on published and widely circulated texts, rarely incorporating lesser-known writings. More recently, scholars have begun to recognize, as significant historical actors in their own right, those authors whose works were not sold in bookshops and who remained in relative obscurity for so long. Their writings deserve to be studied because of how they reveal new modes of geographical mobility and alternative visions of otherness. Before comparing them to texts already included in historical literary canon, these works need to be appreciated on their own terms. From this perspective, the diaries and correspondence of Francophone migrants in the Americas represent a rich source of knowledge. For instance, studies by Yves Frenette and his team have cast letter writing in an entirely new light, by demonstrating the full richness of a source that has long been used by biographers and literary scholars. The study of correspondence and related practices does not merely reveal the mechanisms that allowed letters play a key role in triggering and shaping migratory movements. It also provides a window on the mental universe of both migrants and of those they left behind (see Frenette, Martel and Willis 2006; Fahrni and Frenette 2008).

In contrast to the traditional focus on canonical and widely distributed works, we therefore aim to build an annotated collection of little-known texts, including ones that are only available in public or private archival collections. We also propose to juxtapose different types of documents, in order to identify psycho-sociological variants among travellers and migrants whose movements reflect a diversity of motives.

Indeed, the following are just some of the reasons individuals historically journeyed far from their homes:

- Tourist and leisure travellers were often curious about people and places that may or may not have been easy to reach. For travellers with health issues, this desire to encounter strange peoples and spend time in foreign lands could also be motivated by therapeutic aims. The history of tourism in the nineteenth century and first half of the twentieth century shows that most travellers focused their attention on physical landscapes. This bias relates to a tendency to negate “the other”, as local populations were often reduced to a folkloric trope based on an author’s pre-travel reading and discussions.

- Study provided another reason to travel. In this case, travellers found themselves in urban settings, generally university towns known for their cultural amenities, like Boston or Paris.

- Economic migrations represent a third major category. They could involve either a break with the place of origin, or the conservation of existing ties. A sense of adventure sometimes inspired migrations of this type. However, this was not always the case, and a thrist for adventure figured in other types of travel as well. For example, participants in gold rushes (whether in California, British Columbia or the Yukon, to cite only North American examples) could be driven by the desire to seek both adventure and a fortune.

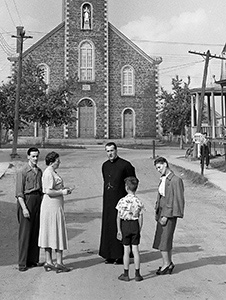

- Political and religious motivations could also prompt population movements, even in the absence of any real threat of persecution. For instance, many French Catholics fled the anticlericalism of the Third Republic, hoping to find a society (Canada or sometimes the United States) that would prove more welcoming to them and their faith. Roles could sometimes be reversed: French republicans (the revolutionaries of 1848, opponents of the Second Empire, the Communards of 1871) were also forced into exile because of their political beliefs, and in some cases faced legal prosecution if they remained at home.

- Other travellers left in search of personal fulfilment. Some sought to advance their education or careers, while others pursued a clear vocation or a utopian vision.

There were therefore a wide range of potential scenarios, especially where social status was concerned. Whereas travel for leisure and study was the preserve of the reasonably well-to-do, other forms of mobility involved poor emigrants seeking their fortune, or at least seeking to live with dignity in a new land. In the case of this second group, immigration flows were all the more significant, since they generally corresponded to the most intense periods of economic crisis in a particular geographic area.

The relationship to language: An indicator of social status

Very often, writing skills reflect an author’s social status. Writers who did not belong to the literary, cultural or social elites had a significantly different relationship to their texts. This does not mean that the travellers we discuss lacked the linguistic capital necessary to make their stories understandable and pleasurable for readers. Moreover, the mastery of the English language demonstrated in narratives of travel or immigration to English-speaking lands provides clear evidence of these travellers’ language abilities. In fact, by the nineteenth century, knowledge of English had already become an effective means of social and professional advancement.

At the same time, these authors’ bilingualism is also reflected in the use of English constructions or vocabulary in their French texts. Indeed, the writings of the French Canadians in our study are rife with Anglicisms. The gold panner Lorenzo Létourneau provides a particularly striking example. We can easily explain this phenomenon: in the first half of the nineteenth century, all segments of French Canadian society were affected by Anglicization. Quebec was a popular destination for British migrants fleeing the social and economic upheavals of the Industrial Revolution, and its English-speaking population grew substantially during the period. Whereas Quebec was home to only 30,000 Anglophones in 1812, their numbers had risen to 200,000 by 1851. By mid-century, they even outnumbered Francophones in Montreal. Although this demographic trend reversed in the decades that followed, English continued to permeate the vocabulary and syntax of French Canadians (and Acadians). At the turn of the twentieth century, despite a growing awareness of the issue among the elites, this process of Anglicization only intensified with the arrival of consumer goods from south of the border and a growing taste for American popular culture. It is even more widespread and deeply felt in the French Canadian diaspora.

Dickinson 2008, 130-42; Frenette 2008, 147-64.

Keeping these socioeconomic factors in mind can protect against developing an overly aesthetic relationship with the narratives. Too often, the material is selected and assessed in terms of the author’s renown. And although we take a different tack, our approach maintains the usual objectives associated with the study of travel narratives. In particular, we treat them as more than just sources of exoticism, since travellers also talk about themselves and their own societies. This back-and-forth between self-examination and examination of the other reflects an author’s efforts to explain the exotic in terms of “the endotic”. In the introduction to “Écrits de voyageurs européens sur le Québec” (Writings of European travellers on Quebec), a special issue of the journal Recherches sociographiques, Gérard Fabre provides a theoretical and methodological framework for understanding this process (Fabre 2013). He also discusses the key historical milestones in transatlantic travel, the challenge of categorizing travel narratives, and the role of the humanities and social sciences in this field. But regardless of the form these writings might take, they all rest on ideological foundations that their authors may or may not openly acknowledge. The result is recurrent cultural stereotypes, which are nevertheless highly diverse, since their level of acceptability varies considerably from one period to the next.

In French Canada, for example, travellers’ writings often reflect the “survival ideology” that historically structures most discourses circulating in Quebec’s public phere:

In a society seeking to preserve its national character, such as French-Canadian society in the nineteenth century, otherness serves to reinforce rather than destabilize identity. Most often, observers use the other’s culture to reinforce their own, and more specifically to uncover traces of their own culture in that of the other (Rajotte 1997, 171—our translation).

Although travellers’ ideological viewpoints can be rebuked within a well-defined semantic field using a rigorous critical approach, scholars’ own viewpoints are also restricted by how, as latter-day observers, they position themselves outside their object of study. By claiming the high ground, they can comfortably pass judgment on a travel narrative and its author. Indeed, this semantic field—connected to what is called “colonial discourse analysis”—is highly susceptible to pejoration. By definition, travel narratives reflect ethnocentric or even colonialist thinking, a doxa that is ripe for indictment. The rebuke of the ideology distilled in a travel narrative therefore involves identifying the stereotypes that predominate within a group, within a community and, even more often, within a nation.

The historization of travel writings inspires reflections on travellers’ attitudes toward the idea of nation. Beginning in the nineteenth century, travellers tended to essentialize the society they visited by presupposing the existence of a nation—or at very least a homogeneous culture that fit the model of a nation. By extension, travellers assigned an essential nature to the people, the social and ethnic groups, and the religious communities that composed the societies they observed. Essentialization involves attributing fundamental identifying qualities to individuals or entities. This amounts to presupposing the existence of an organic whole and a form of timeless continuity that defines and demarcates territories according an ahistorical process. This gives rise to a differentiation between internal identity and external otherness, based on innate understanding.

Critiques of the essentialist approach are not without merit, but they could also be applied to knowledge produced by historians and social scientists, whose disciplines were also institutionalized in the nineteenth century. After all, most of the time, these scholars’ efforts to avoid essentializing collectivities only lead to the euphemization of labels and categories used to describe social groups. The act of naming is essentialist by definition, insofar as it presupposes some degree of temporal continuity and spatial delimitation. Once named, discursively constructed social groups (communities, classes, nations, etc.) become essentialized. Studies that rely on such constructions cannot avoid the pitfalls of essentialization any more (or less) than travel writings.

The historicity of texts describing travel experiences is also reflected in the fluctuating popularity of the corresponding literary genre. In Quebec, the 1880s marked the golden age of travel literature, before the market became flooded in the following decade (Rajotte 1997, 209 and 230). Rather than an entire life, these personal narratives describe periods of migration or travel experiences of varying lengths. They are incomplete, fragmentary, one-sided documents—but their incomplete character is precisely what makes them so rich. The subjective viewpoint of an anonymous or obscure actor provides an account of how a specific part of the world was seen and experienced. This brings to light a microcosm of the collective history in which the author participated.

The multiple, almost infinite discursive registers conveyed through travellers’ voices lay bare the challenge of reconciling “a plurality of itineraries with the singularity of the place of production” (Certeau 1975, 226; 1988, 217-218). These are historical documents, not in the sense that they bear witness to something that is in any way representative, but because of the social meanings that can be assigned to them. In other words, they are fragments of history that we intend to collect here, not because of their literary value (although they may well have some), but because they offer alternative (though not necessarily antagonistic) perspectives that complement official histories and memories.

NOTES

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Legal Deposit (Quebec and Canada),

3rd quarter 2018.

ISBN 978-2-921926-62-1 (PDF)

ISBN 978-2-921926-63-8 (HTML) Credits

Translation Christopher Hinton

Copy editing Steven Watt

Graphic design Émilie Lapierre Pintal

Coordination Mélanie Lanouette

FABRE, Gérard with the collaboration of Yves FRENETTE. 2018. FABRE, Gérard with the collaboration of Yves FRENETTE. 2018. “Travel and Migration Narratives: A New Anthology” In Les récits de voyage et de migration comme modes de connaissance ethnographique: Canada, États-Unis, Europe (XIXe-XXe siècles), edited by Gérard Fabre, Yves Frenette and Mélanie Lanouette. Québec: Centre interuniversitaire d'études québécoises (“Atlas historique du Québec” series) - ). [Online]: https://atlas.cieq.ca/la-francophonie-nord-americaine/travel-and-migration-narratives-a-new-anthology.html (accessed March 13, 2026).