The Formation of the Laurentian Base

By Serge Courville, Claude Boudreau, Normand Séguin, Alain Laberge, Lina Gouger and Michel BoisvertPopulating The Lowlands

By Serge CourvilleStarting in the 17th century, France began to establish a colony on the shores of the St. Lawrence which would quickly become the cradle of a new society. Emerging from a small nucleus of migrants – fewer than 10 000 in total – the colony would create an original landscape, planned by colonial administrators and seigneurs but fashioned by the hands of a population strengthened by various sources of solidarity, notably the family. In less than 150 years, colonists fashioned a unique cultural sphere, distinct from its neighbours. Meanwhile, another geography settled over the original plan for the development of the colony, one which was both more family-based and more intimate. It was the result of the appropriation of the land by households which gave it its unique traits.1

The Progress of Settlement (1667-1784)

The first French settlements on the shores of the St. Lawrence were established on sites which had long been visited by Indigenous peoples. However, by the time of Champlain’s arrival, these populations had almost all disappeared.

After some false starts, a durable colony was founded and, after a few years, three centres of settlement emerged around the present-day cities of Quebec, Trois-Rivières and Montreal. Respectively founded in 1608, 1634 and 1642, these three agglomerations would support the colonization process, as depicted in the maps of 1667 and 1692.

Over the following years and until the end of the French Regime, colonization progressed in stages, eventually forming a long ribbon of settlements stretching along the shores of the St. Lawrence, from the regions downstream from Quebec to those immediately upstream from Montreal, with significant bulges surrounding the two principal settlements. The region of Lake St. Pierre remained the only area left to conquer, due to less favourable physical conditions.

The British Conquest of 1759-1760 did nothing to change this progression. From that date until the final decades of the 18th century, the zone of settlement expanded in two different directions: from the shores of the St. Lawrence toward the interior and, further east on the river’s south shore, downstream from Quebec to the new lands around Rimouski.

As was the case under the French Regime, this expansion was tied to a high birth rate: the population was doubling every 25 years. And because the majority of the population was Roman Catholic and French, the result was a dense cultural sphere which was distinct in North America.

Figure 1Batiscan village on the Official Map of the Parish of St. François-Xavier de Batiscan, County of Champlain, 1876

BANQ-Québec, E21,5105,553,5552,D06-2820.

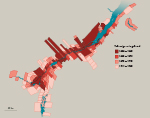

Map 1The Progress of Settlement (1667-1784)

* 168 unlocalised individuals in 1667.

** Beyond the map – The 1765 census also notes 93 individuals in Restigouche, 209 in Baie-des-Chaleurs and 109 in Gaspé.

Internal Administrative Divisions: The French Regime

By Claude Boudreau, Serge Courville and Normand SéguinA century after the founding of Quebec, the colonial administration undertook a vast census of property which showed not only the extent of the population, but also of the colony’s territorial structures. Divided into three governments – those of Quebec, Trois-Rivières and Montreal – the territory was further divided into long bands of land perpendicular to the river, the seigneuries and the censives, which were identified by the name of their owner. These seigneuries had been granted to seigneurs, who received them on the condition of fulfilling certain obligations to the king, and then divided into rangs and lots for colonists, to whom they were granted on the condition of paying certain obligations. This original method of dividing the land is still evident today. It serves as an eloquent reminder of the role of space in the development of the colony.

The initiative for introducing such a system in the St. Lawrence valley fell to the Compagnie des Cent-Associés, created in 1627 by Cardinal de Richelieu. Upon its arrival in Canada in 1633, the company found only one seigneur, who had been granted some 7000 acres of land spread among four fiefs. In short, the territory was essentially unoccupied and unorganized. Thus, it fell to the Cent-Associés, through a series of strategic interventions, to give structure to the young colony. In less than 30 years, the colonial world was structured through the introduction of institutions (the seigneurie, the rang, the Custom of Paris, borrowed from the Vexin province of France) which would facilitate settlement and regulate economic and social life. The establishment of royal government in 1663 completed this work by also introducing new ideas regarding village structures. While these were not entirely absent under the Cent-Associés, they would now take on new functions, more closely related to defence and more compatible with the desire of the king to exert his power over the colony. For example, villages were created in the Quebec City area on the model of Charlesbourg, which had been established by the Jesuits a few years before. But the experiment proved to be a failure. Instead, the size of seigneuries granted by the Cent-Associées was reduced (the largest, the Citière, extended from the south shore of Montreal all the way to New York and even 10 leagues into the sea!). Soon, however, the seigneuries were enlarged once again, but with more modest proportions than before.

Figure 2Map of the Government of Quebec [...], 1709)

Gédéon de Catalogne and Jean-Baptiste de Couagne. Bibliothèque nationale de France, département Cartes et plans, GE SH 18 PF 127 DIV 2 P 2.

The seigneurie primarily structured economic and social life. By contrast, parishes were created to regulate religious life, beginning with the parish of Quebec. It would serve as the headquarters of the Canadian episcopate and was attached to the diocese of Quebec, which had been created in 1659 and was the only diocese existing at the time. Later, several others parishes were founded, so many that in 1721 a general inquiry was ordered on the state of parish affairs, with the goal of better managing their growth. As well as confirming the borders of existing parishes, the inquiry laid out the boundaries for new parishes as well. In all, 126 parishes were created during the French Regime, including a dozen which disappeared when they were amalgamated with others when parish boundaries were reorganized. Those which survived these changes would remain in operation.

Though a more recent creation, the parish would rapidly replace the seigneurie as the framework for economic and social life, especially since many seigneurs did not yet live in their seigneurie. Guided by the parish priest and the militia captain, everyday parish administration was the responsibility of an elected council of church wardens. This made the parish not only a more democratic institution, but also one which was more in touch with local realities. However, from a broader perspective, the geometry of seigneurial boundaries continued to define the dense cultural sphere which was emerging in the St. Lawrence Valley.

Figure 3Official Map of the Parish of St. François-Xavier de Batiscan, County of Champlain, 1876

BANQ-Québec, E21,5105,553,5552,D06-2820.

The Expansion and the Formation of Settlement

By Alain Laberge, Lina Gouger and Michel BoisvertThe process of shaping the settled area of the seigneuries continued over a period of about 150 years, with fluctuations and periods of varying intensity over time. Under the administration of the Compagnie des Cent-Associés (up until 1663), seigneurial concessions reflected the importance of the urban centres of Quebec, Trois-Rivières and Montreal, and resulted in a settled area which was rather spread out and unbalanced. From 1672 and up until the Edicts of Marly in 1711, concessions continued at a regular pace, gradually filling in the empty spaces along the shores of the St. Lawrence. Seigneurial concessions began again at the end of the 1720s. They were characterized by the development of new areas of settlement, principally along the upper Richelieu and Chaudière Rivers and by extending the depth of the settlements through the concession of lands in the interior. The concession of seigneurial lands stopped with the end of the French Regime.

Settlement in the St. Lawrence Valley in 1725

On the whole, the area of settlement in 1725 formed a long, unbroken ribbon on both sides of the St. Lawrence between Montreal and Quebec, extending even further downstream on the south shore. Despite this continuous occupation of the shoreline, the situation varied greatly in specific governments, regions, and seigneuries. Thus, the government of Trois-Rivières was less settled than those of Montreal and Quebec. The same was true for the south shore of Quebec, when compared to the neighbouring region of the Côte-du-Sud. Within individual seigneuries, there was a staggering variety of situations, from an overpopulated Île d’Orléans to the Côte de Beaupré whose potential was limited by the barriers posed by the Canadian Shield. There were seigneuries containing only a few good parcels of land and others which contained several dozen or even upwards of a hundred. Everywhere, however, whatever the rhythm and intensity of settlement, the seigneurial settlements still constituted a vast pioneer frontier.

Figure 4View of De Chambaut on the River St Laurence above Quebec, 1765

Lord Adam Gordon. British Library, Maps K.Top.119.43.7.

Map 2The formation of settlement (1626-1762)

Map 3Settlement in the St Lawrence valley in 1725

The Patterns of Land Occupation

The manner in which the territory was divided reveals the dominance of the coastal settlement model, characterized by the alignment of lands on each fief’s river frontage. This “classic” model was applied in two seigneuries out of three. Many of the waterways which snaked their way across the seigneuries had a determining influence on the patterns of occupation. They could become a major nexus for orienting settlement, as in the case of Batiscan.

Figure 5The Seigneurie of Batiscan, 1725

LAC, Series G1, vol. 961. NMC1725.

Notes

- The original French versions of theses texts were first published in Serge Courville (ed.), Population et territoire (Québec: Presses de l’Université Laval, 1996) and in Claude Boudreau, Serge Courville and Normand Séguin, Le territoire (Québec: Presses de l’Université Laval, 1997).

BIBLIOGRAPHY

All rights reserved. Centre interuniversitaire d’études québécoises (CIEQ)

Legal Deposit (Quebec and Canada), Q1 2023.

ISBN 978-2-921926-80-5 (PDF)

Credits

- TRANSLATION – Steven Watt

- Graphic design – Émilie Lapierre Pintal with the collaboration of Marie-Claude Rouleau (Élan création)

- Coordination – Sophie Marineau

- Cartography (MAP 1) – Louise Marcoux (Laboratoire de cartographie de l’Université Laval) and Émilie Lapierre Pintal. The map is an adaption of the original map published in Population et territoire.

- Programming – Adam Lemire with the collaboration of Tomy Grenier and Jean-François Hardy

How to cite this paper

COURVILLE, Serge. 2023. The Formation of the Laurentian Base. Québec: Les Presses de l'Université Laval (“Atlas historique du Québec” series). [Online]: https://atlas.cieq.ca/historical-atlas/interactif/the-formation-of-the-laurentian-base.html (accessed February 25, 2026).